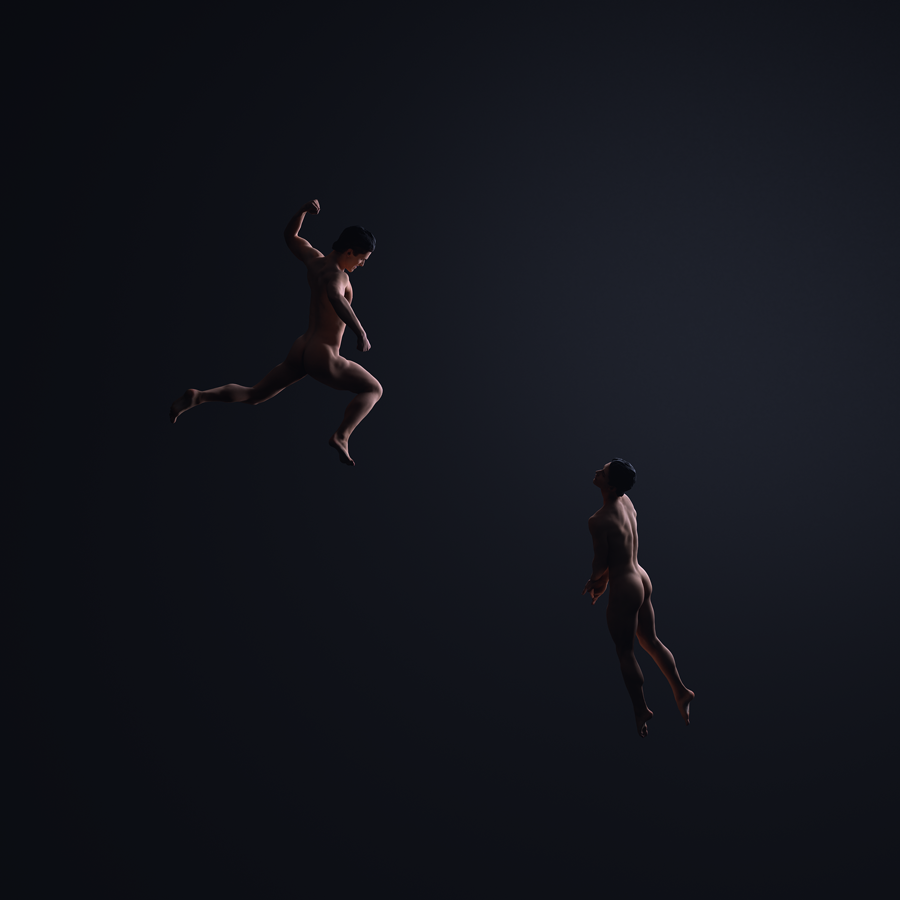

Gilgamesh

By Jack Symonds & Louis Garrick

World Premiere

The world’s oldest poem. Opera’s most cutting-edge artists.

Opera Australia, Sydney Chamber Opera and Carriageworks present Gilgamesh, in association with Australian String Quartet and Ensemble Offspring.

The ancient and contemporary collide to dazzling effect in this world premiere.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is humanity’s oldest epic written poem. Emerging from ancient Mesopotamian mythology, it tells of a restless young king who, through experiences of love and loss, becomes a better person. His unexpected love for a half-man, half-animal leads him wide-eyed into mysterious realms.

Gilgamesh’s story sings to us across millennia, and this brand-new opera uncovers all that remains strikingly relevant: its approach to mortality, sexuality and our relationship with nature. This is the first opera in English based upon this foundational part of civilisation.

Composed by Sydney Chamber Opera Artistic Director Jack Symonds and brought to Carriageworks’ vast performance space by visionary director Kip Williams (Sydney Theatre Company’s The Picture of Dorian Gray), Gilgamesh is an epic that must be experienced.

Singing scorpions share the stage with a Bull of Heaven and oracles interpreting the flood which swept the Earth.

This is Opera Australia’s first collaboration with Sydney Chamber Opera, a company renowned for presenting “an astonishing new vision of what contemporary opera can achieve” (Time Out). Two outstanding chamber music ensembles bring a collective virtuosity to this colourful new score: Australian String Quartet and Ensemble Offspring.

Symonds conducts a cast of Australian contemporary opera specialists. Jeremy Kleeman and Mitchell Riley play Gilgamesh and the beast Enkidu, joined by Jane Sheldon, Jessica O’Donoghue and Daniel Szesiong Todd.

Composer

Jack Symonds

Libretto

Louis Garrick

Conductor

Jack Symonds

Director

Kip Williams

Set Designer

Elizabeth Gadsby

Costume Designer

David Fleischer

Lighting Designer

Amelia Lever-Davidson

Electronics & Sound Designer

Benjamin Carey

Assistant Director

Tait de Lorenzo

Singers

Gilgamesh

Jeremy Kleeman

Enkidu

Mitchell Riley

Ishtar/Scorpion

Jane Sheldon

Shamhat/Uta-Napishti/Scorpion

Jessica O’Donoghue

Humbaba/Ur-Shanabi

Daniel Szesiong Todd

Australian String Quartet

Dale Barltrop: Violin I

Francesca Hiew: Violin II

Christopher Cartlidge: Viola

Michael Dahlenburg: Cello

Ensemble Offspring

Claire Edwardes: Percussion

Lamorna Nightingale: Flute/ Piccolo/ Alto Flute/ Bass Flute

Jason Noble: Contrabass Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet/ Clarinet

Jacob Abela: Piano/ Keyboard

Jasper Ly: Oboe/ Cor Anglais

Benjamin Ward: Double Bass

Melina van Leeuwen: Harp

Opera Australia, Sydney Chamber Opera and Carriageworks present Gilgamesh, in association with Australian String Quartet and Ensemble Offspring.

![]()

SCO wishes to thank the generous donors who have made this production possible:

Lead Patron

Judith Neilson AM

Executive Production Partners

Anonymous (2), John Barrer, Penelope Seidler AM, Kim Williams AM

Principal Artist Partners

Anonymous (1), Dr. Robert Mitchell, Prof. Emerita Di Yerbury AO

Artist Partners

Andrew Cameron AM & Cathy Cameron, John Kaldor AO, John Garran, Perpetual Foundation: The Meredith Brooks Endowment, The Russell Mills Foundation, Jane Rotsey, Christine Williams, James Williams

Associate Artist Partners

Andrew Andersons AO, William Brooks & Alasdair Beck, Glynis Johns, Dr. Merilyn Sleigh, Gil Appleton, Julian Lloyd-Phillips, Trish Richardson in memory of Andy Lloyd James

Donors

Antoinette Albert, Angela Bowne SC, Phillip Cornwell, Elizabeth Evatt AC, Vicki Fraser, Josephine Key, Brendan McPhillips, Janet Nash, Elizabeth Nield, Trevor Parkin, Joel Roast, David Robb,